Every now and then one can find some truly useful information on Wikipedia. This list of the world's Independence Days, sent to Tory Historian by a well-wisher, is one of them. It has all the national flags as well, which is an added bonus.

As usual, Tory Historian will produce the odd blog or two on the subject but it is worth reminding readers in or near London of this wonderful event. If I may make a suggestion, try to buy the whole booklet of what is open in some friendly bookshop (too late to do so on line) rather than try to figure out what to do and where to go from the website. Happy hunting!

Tory Historian has never quite understood why the bien pensants otherwise known as people who never read detective stories, considering them to be inferior, but like pontificating consider Agatha Christie's novels to be particularly unrealistic. It is true that criminals are not always brought to justice (and they are not always in her novels either) but that is the premiss of that most conservative of genres, the detective story.

Tory Historian has never quite understood why the bien pensants otherwise known as people who never read detective stories, considering them to be inferior, but like pontificating consider Agatha Christie's novels to be particularly unrealistic. It is true that criminals are not always brought to justice (and they are not always in her novels either) but that is the premiss of that most conservative of genres, the detective story.

It is also true that she is often slapdash and cavalier about certain details, in particular dates, time spans, ages. All of that annoys Tory Historian as readers can imagine. This is so different from the silly but precise novels by Georgette Heyer. But when it comes to descriptions of life and social mores she is far more realistic and accurate than her contemporaries Ngaio Marsh or Margery Allingham.

The accusations that she wrote about large country houses and aristocratic families and parties is completely untrue. Her milieu was the middle class, her people almost entirely professionals, lawyers, doctors, clergymen, the occasional businessman, maybe members of the squierarchy like Colonel Bantry. That is why she managed to write well about changes in social life. The village in A Murder is Announced is very different from the village of Murder in the Vicarage. The people who may have had a couple of servants before the Second World War have maybe a foreign refugee, a cleaning woman or an au pair after it. The large households either disappear or are reinvented to suit some Hollywood star. All very realistic.

People who consider Raymond Chandler to be more realistic have, one assumes, read neither author but have dimly heard the expression about the man in the mean streets. Murder happens in mean streets and in well-appointed homes or flats shared by three middle-class girls. Are those convoluted, incomprehensible plots of Chandler's, full of wisecracking people truly realistic? Hardly.

So we come to Tory Historian's reading matter of the day and that is John Curran's Agatha Christie's Secret Notebooks. Some interesting stuff about the way Christie developed her plots though after a while one loses interest in the minutiae of literary invention. There are also two stories that have never been published before, one called The Incident of the Dog's Ball, which, Mr Curran works out, was probably written in 1933 but never offered to Christie's agent. Readers of her novels will instantly recall one of her best, Dumb Witness, published in 1937. Mr Curran thinks the story was withheld because the author decided almost immediately to turn it into a novel. That seems a little odd. After all, Yellow Iris, which became Sparkling Cyanide, was published and Mr Curran lists several others. On the whole, Christie's novels are better than her short stories, entertaining though these often are. In that respect she is the opposite of Conan Doyle.

The Incident of the Dog's Ball is not bad but Dumb Witness is excellent if one forgets about the peculiar incident of Captain Hastings and the dog. At the beginning of the novel Hastings explains that he has just come back from Argentina, leaving his wife "Cinderella" Dulcie to manage the ranch while he deals with business matters in England. By the end of the novel he seems to have acquired a dog, settled back into English life an forgotten all about his wife, his ranch and Argentina. (Yet we know from later novels that he does go back. Most mysterious.)

The story does, however, show village life of the period in brisk and amusing fashion as is Christie's wont. In particular she destroys the myth of the wonderful food one could have in country inns and pubs back in the good old days, whenever these might have been. This is what Captain Hastings says:

Little Hemel we found to be a charming village, untouched in the miraculous way that villages can be when they are two miles from a main road. There was a hostelry called The George, and there we had lunch - a bad lunch I regret to say, as is the way at country inns.What wealth of suffering and realism lies in that last phrase.

Here are a few questions to mull over: Which was the largest popular political organization in this country? Which political organization first ensured that membership was open to all classes and people of all incomes? Which political organization involved public activity by women of all classes and in large numbers? Which political organization first had events, both social and educational, for children and young people? [The picture below is of a group of Headington Buds.] Which political organization set up co-operative funds to help those of their members who were less well off?

Here are a few questions to mull over: Which was the largest popular political organization in this country? Which political organization first ensured that membership was open to all classes and people of all incomes? Which political organization involved public activity by women of all classes and in large numbers? Which political organization first had events, both social and educational, for children and young people? [The picture below is of a group of Headington Buds.] Which political organization set up co-operative funds to help those of their members who were less well off?

As the debate about education and its failings rages and as new attempts are made to counter what is seen as the pernicious influence of various educational theories, it is useful to look back on what was said in the past. David Linden, a Ph.D. student at King's College, London, whose interests lie in the modern day Conservative Party looks at a previous educational debate in the sixties and seventies, when the authors of the Black Papers on Education clashed with the educational establishment.

There is always something interesting in History Today. Sometimes it is very little but always something. Today's e-mail brought two links that were worth following up.

Readers of this blog might like to find some more omissions.

If ever there was a conservative writer of detective stories it was Cyril Hare, a.k.a. Alfred Alexander Clark, a County Court judge, even if an aunt of his seems to have been a socialist politician. (Well, a Labour politician, at least, one of the large group of wealthy non-working class socialists, ever present in the Labour Party.)

Many people know what the Whig interpretation of history is, if only in the hilariously parodic version of 1066 And All That, a book I always recommend to anyone who wants a quick summary of English history. (Here is a link to the text but, really, one needs the book in front of one because of the illustrations and because it is easier to shed tears of laughter over a book than in front of a screen.)

Many people know what the Whig interpretation of history is, if only in the hilariously parodic version of 1066 And All That, a book I always recommend to anyone who wants a quick summary of English history. (Here is a link to the text but, really, one needs the book in front of one because of the illustrations and because it is easier to shed tears of laughter over a book than in front of a screen.)

In "The Life and Thought of Herbert Butterfield," Michael Bentley draws on a range of private letters and papers to sharpen our appreciation of Butterfield's actual accomplishments, particularly "The Whig Interpretation of History," the 1931 book that made his reputation by forcing historians to reconsider their discipline. Butterfield argued forcefully against the then-common practice of honing a historical narrative so that it neatly progresses, seemingly inevitably, to the enlightened present or tailoring descriptions of the past to reflect contemporary concerns.While it seems sensible not to stick to the view of history, especially that of England and Britain, being a more or less clearly ascending line towards a sensible and progressive society, it cannot be said that the alternative teaching that has developed since the Whig theory has been abandoned, has been an improvement.

By discarding the apparent linear progression of history schools, teachers and, above all, creators of the national curriculum and examination topics, have discarded all narrative. That, in turn, has meant a loss of understanding as it is impossible to grasp what certain events might mean if the background to them is unknown; and a loss of interest for most pupils. How can one be interested in history if it consists of disconnected topics of varying interest and importance? Ironically, while Butterfield's name is all but unknown these days, Our Island Story, the pre-eminent children's book that was so ably parodied by 1066 And All That, was, on its reprinting, a huge success. As a matter of fact, it is not a very good book and its over-reliance on Shakespeare's plays for information is regrettable. But it gives what many children need: a story in an attractive format with many exciting illustrations.

The review does make one want to read the biography itself, which, clearly deals with the difficult aspects of Butterfield's life while presenting the argument for a reappraisal of his work.

Links

Followers

Labels

- 1922 Committee (1)

- abolition of slave trade (1)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- academics (2)

- Adam Smith (2)

- advertising (1)

- Agatha Christie (4)

- American history (33)

- ancient history (4)

- Anglo-Boer Wars (1)

- Anglo-Dutch wars (1)

- Anglo-French Entente (1)

- Anglo-Russian Convention (2)

- Anglosphere (19)

- anniversaries (175)

- Anthony Price (1)

- archaelogy (8)

- architecture (8)

- archives (3)

- Argentina (1)

- Ariadne Tyrkova-Williams (1)

- art (14)

- Arthur Ransome (1)

- arts funding (1)

- Attlee (2)

- Australia (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Baroness Park of Monmouth (1)

- battles (11)

- BBC (5)

- Beatrice Hastings (1)

- Bible (3)

- Bill of Rights (1)

- biography (21)

- birthdays (11)

- blogs (10)

- book reviews (8)

- books (78)

- bred and circuses (1)

- British Empire (7)

- British history (1)

- British Library (9)

- British Museum (4)

- buildings (1)

- businesses (1)

- calendars (1)

- Canada (2)

- Canning (1)

- Castlereagh (2)

- cats (1)

- censorship (1)

- Charles Dickens (3)

- Charles I (1)

- Chesterton (1)

- CHG meetings (9)

- children's books (2)

- China (2)

- Chips Channon (4)

- Christianity (1)

- Christmas (1)

- cities (1)

- City of London (2)

- Civil War (6)

- coalitions (2)

- coffee (1)

- coffee-houses (1)

- Commonwealth (1)

- Communism (15)

- compensations (1)

- Conan Doyle (5)

- conservatism (24)

- Conservative Government (1)

- Conservative historians (4)

- Conservative History Group (10)

- Conservative History Journal (23)

- Conservative Party (25)

- Conservative Party Archives (1)

- Conservative politicians (22)

- Conservative suffragists (5)

- constitution (1)

- cookery (5)

- counterfactualism (1)

- country sports (1)

- cultural propaganda (1)

- culture wars (1)

- Curzon (3)

- Daniel Defoe (2)

- Denmark (1)

- detective fiction (31)

- detectives (19)

- diaries (7)

- dictionaries (1)

- diplomacy (2)

- Disraeli (12)

- documents (1)

- Dorothy L. Sayers (5)

- Dorothy Sayers (5)

- Dostoyevsky (1)

- Duke of Edinburgh (1)

- Duke of Wellington (14)

- East Germany (1)

- Eastern Question (1)

- economic history (1)

- Economist (2)

- economists (2)

- Edmund Burke (7)

- education (3)

- Edward Heath (2)

- elections (5)

- Eliza Acton (1)

- engineering (3)

- English history (56)

- English literature (34)

- enlightenment (3)

- enterprise (1)

- Eric Ambler (1)

- espionage (2)

- European history (4)

- Evelyn Waugh (1)

- events (22)

- exhibitions (12)

- Falklands (3)

- fascism (1)

- festivals (2)

- films (13)

- food (7)

- foreign policy (3)

- foreign secretaries (2)

- fourth plinth (1)

- France (1)

- Frederick Burnaby (1)

- French history (3)

- French Revolution (1)

- French wars (1)

- funerals (2)

- gardeners (1)

- gardens (3)

- general (17)

- general history (1)

- Geoffrey Howe (2)

- George Orwell (2)

- Georgians (3)

- German history (3)

- Germany (1)

- Gertrude Himmelfarb (1)

- Gibraltar (2)

- Gladstone (2)

- Gordon Riots (1)

- Great Fire of London (1)

- Great Game (4)

- grievances (1)

- Guildhall Library (1)

- Gunpowder Plot (3)

- H. H. Asquith (1)

- Habsbugs (1)

- Hanoverians (1)

- Harold Macmillan (1)

- Hatfield House (1)

- Hayek (1)

- Hilaire Belloc (1)

- historians (38)

- historic portraits (6)

- historical dates (10)

- historical fiction (1)

- historiography (5)

- history (3)

- history of science (2)

- history teaching (8)

- History Today (12)

- history writing (1)

- hoaxes (1)

- Holocaust (1)

- House of Commons (10)

- House of Lords (1)

- Human Rights Act (1)

- Hungary (1)

- Ian Gow (1)

- India (2)

- Intelligence (1)

- IRA (2)

- Irish history (1)

- Isabella Beeton (1)

- Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1)

- Italy (1)

- Jane Austen (1)

- Jill Paton Walsh (1)

- John Buchan (4)

- John Constable (1)

- John Dickson Carr (1)

- John Wycliffe (1)

- Jonathan Swift (1)

- Josephine Tey (1)

- journalists (2)

- journals (2)

- jubilee (1)

- Judaism (1)

- Jules Verne (1)

- Kenneth Minogue (1)

- Korean War (2)

- Labour government (1)

- Labour Party (1)

- Lady Knightley of Fawsley (2)

- Leeds (1)

- legislation (1)

- Leicester (1)

- libel cases (1)

- Liberal-Democrat History Group (1)

- liberalism (2)

- Liberals (1)

- libraries (6)

- literary criticism (2)

- literary magazines (1)

- literature (7)

- local history (2)

- London (14)

- Londonderry family (1)

- Lord Acton (2)

- Lord Alfred Douglas (1)

- Lord Hailsham (1)

- Lord Leighton (1)

- Lord Randolph Churchill (3)

- Lutyens (1)

- magazines (3)

- Magna Carta (7)

- manuscripts (1)

- maps (9)

- Margaret Thatcher (21)

- media (2)

- memoirs (1)

- memorials (3)

- migration (1)

- military careers (1)

- monarchy (12)

- Munich (1)

- Museum of London (1)

- museums (5)

- music (7)

- musicals (1)

- Muslims (1)

- mythology (1)

- Napoleon (3)

- national emblems (1)

- National Portrait Gallery (2)

- nationalism (1)

- naval battles (3)

- Nazi-Soviet Pact (1)

- Nelson Mandela (1)

- Neville Chamberlain (2)

- newsreels (1)

- Norman conquest (1)

- Norman Tebbit (1)

- obituaries (25)

- Oliver Cromwell (1)

- Open House (1)

- operetta (1)

- Oxford (1)

- Palmerston (1)

- Papacy (1)

- Parliament (3)

- Peter the Great (1)

- philosophers (2)

- photography (3)

- poetry (5)

- poets (6)

- Poland (3)

- political thought (8)

- politicians (4)

- popular literature (3)

- portraits (7)

- posters (1)

- President Eisenhower (1)

- prime ministers (27)

- Primrose League (4)

- Princess Lieven (2)

- prizes (3)

- propaganda (8)

- property (3)

- publishing (2)

- Queen Elizabeth II (5)

- Queen Victoria (1)

- quotations (31)

- Regency (2)

- religion (2)

- Richard III (6)

- Robert Peel (1)

- Roman Britain (3)

- Ronald Reagan (4)

- Royal Academy (1)

- royalty (9)

- Rudyard Kipling (1)

- Russia (10)

- Russian history (2)

- Russian literature (1)

- saints (7)

- Salisbury (6)

- Samuel Johnson (1)

- Samuel Pepys (1)

- satire (1)

- scientists (1)

- Scotland (1)

- sensational fiction (1)

- Shakespeare (16)

- shipping (1)

- Sir Alec Douglas-Home (1)

- Sir Charles Napier (1)

- Sir Harold Nicolson (6)

- Sir Laurence Olivier (1)

- Sir Robert Peel (3)

- Sir William Burrell (1)

- Sir Winston Churchill (17)

- social history (2)

- socialism (2)

- Soviet Union (6)

- Spectator (1)

- sport (1)

- spy thrillers (1)

- St George (1)

- St Paul's Cathedral (1)

- Stain (1)

- Stalin (3)

- Stanhope (1)

- statues (4)

- Stuarts (3)

- suffragettes (3)

- Tate Britain (2)

- terrorism (4)

- theatre (4)

- Theresa May (1)

- thirties (2)

- Tibet (1)

- TLS (1)

- Tocqueville (1)

- Tony Benn (1)

- Tories (1)

- trade (1)

- treaties (1)

- Tudors (2)

- Tuesday Night Blogs (1)

- Turkey (3)

- Turner (2)

- TV dramatization (1)

- twentieth century (2)

- UN (1)

- utopianism (1)

- Versailles Treaty (1)

- veterans (2)

- Victorians (13)

- War of Independence (1)

- Wars of the Roses (1)

- Waterloo (5)

- websites (7)

- welfare (1)

- Whigs (4)

- William III (1)

- William Pitt the Younger (4)

- women (11)

- World War I (20)

- World War II (54)

- WWII (1)

- Xenophon (1)

Counters

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(115)

-

▼

September

(9)

- Tory Historian's blog - Independence

- Events - Open House week-end

- Tory Historian's blog- Christie was highly realistic

- Book review - The greatest popular political organ...

- A look back on past educational debates

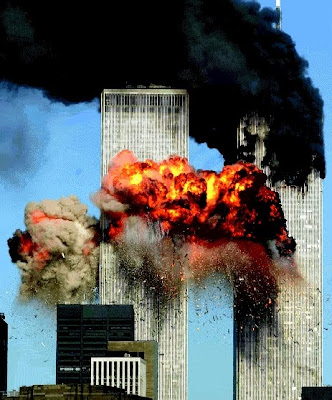

- Tory Historian's blog - Defiance September 2001

- Tory Historian's blog - Two links from History Today

- Tory Historian's blog - Cyril Hare

- The man who defined Whig history

-

▼

September

(9)